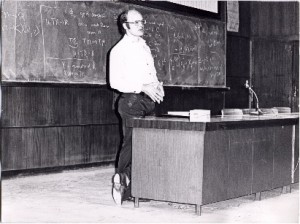

If you’re involved in the process of trying to move information from your head into other heads (aka “learning” or “teaching” or “training” or “edumacating”) you probably began with the simplest form –

the lecture. Open mouth, spew words, hope recipient can hear and understand and process and retain information. You used this model because for twelve years (or more) that’s the way you were taught in formal education.

the lecture. Open mouth, spew words, hope recipient can hear and understand and process and retain information. You used this model because for twelve years (or more) that’s the way you were taught in formal education.

And learners like lectures. They’re passive, and don’t require much. It’s easy to zone out, thinking about the weekend and having some fun. There’s little risk of looking stupid, or giving a wrong answer. Somebody else is driving, and you’re just along for the ride. All you have to do is keep your eyes open, avoid drooling, and ask a few easy softball questions at the end.

“So tell me, Professor Canhardly, since you wrote the text we’re using does that mean that you’d heartily endorse all the concepts and theories therein?”

Speaking as a presenter, we like lectures too! You all have to look at us up here in the front of the room, and pretend that what we’re saying is important. We get to decide what’s important, and what’s not. We get to make the lame jokes, and you have to pretend to laugh. And if you ask a difficult question, we get to deflect it or claim that it’s outside the bounds of our subject for today.

So — What’s The Problem?

The problem is (you just KNEW there was going to be a problem here, didn’t you?) that lectures aren’t very effective at long-term transfer of information from one humanoid to another. They’re pretty good if all you want to do is just jam some random facts in a head, take a test, and then forget it forever. Or if you’re just trying to get an evaluation that says “Dr. Neverdidt was really funny and told good stories”.

Here’s a simple example — if you’re headed out to the airport today, would you choose the pilot who’s heard a LECTURE on how to fly, or the pilot who’s actually FLOWN before?

Of course you’d want the guy who’d had some time actually doing the task, in addition to hearing someone talk about it. And, in a nutshell, that’s why lectures really can’t do much more than give you a really nice overview of a topic. In the learning world, we’ve got a way to measure what level of actual “doing” you’re going to have after we’ve taught you something — it’s called “Bloom’s Taxonomy“. (A “taxonomy” is just a fancy word for a classification system — like the Dewey Decimal System at the library or the way butchers grade meat at the grocery store.)

Dr. Bloom ranked the learner’s ability to do something on six levels, and gave them names — and then provided examples and descriptive words to go along with — like so:

Category |

Example and Key Words |

| Knowledge: Recall data or information. | Examples: Recite a policy. Quote prices from memory to a customer. Knows the safety rules.Key Words: defines, describes, identifies, knows, labels, lists, matches, names, outlines, recalls, recognizes, reproduces, selects, states. |

| Comprehension: Understand the meaning, translation, interpolation, and interpretation of instructions and problems. State a problem in one’s own words. | Examples: Rewrites the principles of test writing. Explain in one’s own words the steps for performing a complex task. Translates an equation into a computer spreadsheet.Key Words: comprehends, converts, defends, distinguishes, estimates, explains, extends, generalizes, gives Examples, infers, interprets, paraphrases, predicts, rewrites, summarizes, translates. |

| Application: Use a concept in a new situation or unprompted use of an abstraction. Applies what was learned in the classroom into novel situations in the work place. | Examples: Use a manual to calculate an employee’s vacation time. Apply laws of statistics to evaluate the reliability of a written test.Key Words: applies, changes, computes, constructs, demonstrates, discovers, manipulates, modifies, operates, predicts, prepares, produces, relates, shows, solves, uses. |

| Analysis: Separates material or concepts into component parts so that its organizational structure may be understood. Distinguishes between facts and inferences. | Examples: Troubleshoot a piece of equipment by using logical deduction. Recognize logical fallacies in reasoning. Gathers information from a department and selects the required tasks for training.Key Words: analyzes, breaks down, compares, contrasts, diagrams, deconstructs, differentiates, discriminates, distinguishes, identifies, illustrates, infers, outlines, relates, selects, separates. |

| Synthesis: Builds a structure or pattern from diverse elements. Put parts together to form a whole, with emphasis on creating a new meaning or structure. | Examples: Write a company operations or process manual. Design a machine to perform a specific task. Integrates training from several sources to solve a problem. Revises and process to improve the outcome.Key Words: categorizes, combines, compiles, composes, creates, devises, designs, explains, generates, modifies, organizes, plans, rearranges, reconstructs, relates, reorganizes, revises, rewrites, summarizes, tells, writes. |

| Evaluation: Make judgments about the value of ideas or materials. | Examples: Select the most effective solution. Hire the most qualified candidate. Explain and justify a new budget.Key Words: appraises, compares, concludes, contrasts, criticizes, critiques, defends, describes, discriminates, evaluates, explains, interprets, justifies, relates, summarizes, supports. |

Source: http://www.skagitwatershed.org/~donclark/hrd/bloom.html

So, any time you want to teach somebody something, you can think about measuring what they can do based on these six levels. They range from very low “knowledge” to very high “evaluation”. To make that a little easier to understand, let’s try a couple of examples.

Suppose your job was to teach people to tie their tennis shoes. Here’s what that might look like in the different levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy:

|

Knowledge: Recall data or information. |

Can identify tennis shoes from loafers. |

|

Comprehension: Understand the meaning, translation, interpolation, and interpretation of instructions and problems. State a problem in one’s own words. |

Can explain why it’s important to tie shoes correctly (“fall down – go boom!”) |

|

Application: Use a concept in a new situation or unprompted use of an abstraction. Applies what was learned in the classroom into novel situations in the work place. |

Can demonstrate how to tie shoes. |

|

Analysis: Separates material or concepts into component parts so that its organizational structure may be understood. Distinguishes between facts and inferences. |

Can compare how to tie tennis shoes and boots with hooks and loops. |

|

Synthesis: Builds a structure or pattern from diverse elements. Put parts together to form a whole, with emphasis on creating a new meaning or structure. |

Can devise how long laces must be by counting number of holes, calf size and knotting/lacing model. |

|

Evaluation: Make judgments about the value of ideas or materials. |

Can compare and contrast use of rawhide laces, nylon laces, catgut and cotton to recommend the best choice for each situation. |

One more example? How about that jet pilot, learning to deal with losing an engine…

|

Knowledge: Recall data or information.

|

Can list the basic steps in engine restart. |

|

Comprehension: Understand the meaning, translation, interpolation, and interpretation of instructions and problems. State a problem in one’s own words.

|

Can give examples of why an engine may have failed, and probable causes. |

|

Application: Use a concept in a new situation or unprompted use of an abstraction. Applies what was learned in the classroom into novel situations in the work place.

|

Can demonstrate the “Hot Engine Restart” procedure in the flight simulator. |

|

Analysis: Separates material or concepts into component parts so that its organizational structure may be understood. Distinguishes between facts and inferences.

|

Can analyze cockpit instrumentation to determine most likely cause of failure and choose best restart mode. |

|

Synthesis: Builds a structure or pattern from diverse elements. Put parts together to form a whole, with emphasis on creating a new meaning or structure.

|

Can combine engine-out experiences to generate emergency plan for unforeseen circumstances. |

|

Evaluation: Make judgments about the value of ideas or materials.

|

Can land plane in the Hudson River and have every single person walk away alive. |

So, this is why it’s sometimes important to think a little bit further than just lecturing to people about what it is that you want them to know. And that means things like getting their little fingers dirty, testing out concepts, discussing and experimenting, role-playing, tearing it apart, putting it back together, breaking it, fixing it, building a completly new model — all the stuff that takes more time and costs more money.

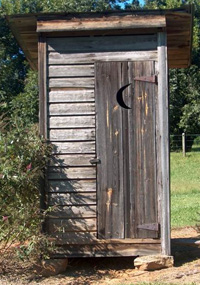

Many years ago, we all headed outdoors to do our business. There was a little house with a half-moon on the door and a Sears catalog. That worked just fine, until the whole idea of indoor plumbing came along and pretty soon there wasn’t much of a market for outhouse manufacturers. It didn’t mean that they weren’t high-quality outhouses, or that the people who built them didn’t care a lot about their product.

Many years ago, we all headed outdoors to do our business. There was a little house with a half-moon on the door and a Sears catalog. That worked just fine, until the whole idea of indoor plumbing came along and pretty soon there wasn’t much of a market for outhouse manufacturers. It didn’t mean that they weren’t high-quality outhouses, or that the people who built them didn’t care a lot about their product. Yeah, part of getting sessions accepted is a catchy title — but I really believe that most everything we’ve taught our students about content in their formal educational history is wrong. How we design it, how we deploy it, how they interact with it and how we judge if they’ve taken it in successfully.

Yeah, part of getting sessions accepted is a catchy title — but I really believe that most everything we’ve taught our students about content in their formal educational history is wrong. How we design it, how we deploy it, how they interact with it and how we judge if they’ve taken it in successfully.

(To make things interesting, they keep changing the name of their discipline. Recent ones have included “Human Potential” and “Human Capital” — bleech!)

(To make things interesting, they keep changing the name of their discipline. Recent ones have included “Human Potential” and “Human Capital” — bleech!) So how about if you consider becoming a

So how about if you consider becoming a