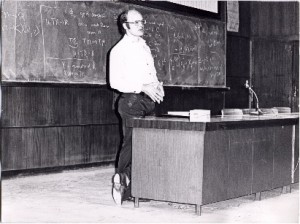

If you’re involved in the process of trying to move information from your head into other heads (aka “learning” or “teaching” or “training” or “edumacating”) you probably began with the simplest form –

the lecture. Open mouth, spew words, hope recipient can hear and understand and process and retain information. You used this model because for twelve years (or more) that’s the way you were taught in formal education.

the lecture. Open mouth, spew words, hope recipient can hear and understand and process and retain information. You used this model because for twelve years (or more) that’s the way you were taught in formal education.

And learners like lectures. They’re passive, and don’t require much. It’s easy to zone out, thinking about the weekend and having some fun. There’s little risk of looking stupid, or giving a wrong answer. Somebody else is driving, and you’re just along for the ride. All you have to do is keep your eyes open, avoid drooling, and ask a few easy softball questions at the end.

“So tell me, Professor Canhardly, since you wrote the text we’re using does that mean that you’d heartily endorse all the concepts and theories therein?”

Speaking as a presenter, we like lectures too! You all have to look at us up here in the front of the room, and pretend that what we’re saying is important. We get to decide what’s important, and what’s not. We get to make the lame jokes, and you have to pretend to laugh. And if you ask a difficult question, we get to deflect it or claim that it’s outside the bounds of our subject for today.

So — What’s The Problem?

The problem is (you just KNEW there was going to be a problem here, didn’t you?) that lectures aren’t very effective at long-term transfer of information from one humanoid to another. They’re pretty good if all you want to do is just jam some random facts in a head, take a test, and then forget it forever. Or if you’re just trying to get an evaluation that says “Dr. Neverdidt was really funny and told good stories”.

Here’s a simple example — if you’re headed out to the airport today, would you choose the pilot who’s heard a LECTURE on how to fly, or the pilot who’s actually FLOWN before?

Of course you’d want the guy who’d had some time actually doing the task, in addition to hearing someone talk about it. And, in a nutshell, that’s why lectures really can’t do much more than give you a really nice overview of a topic. In the learning world, we’ve got a way to measure what level of actual “doing” you’re going to have after we’ve taught you something — it’s called “Bloom’s Taxonomy“. (A “taxonomy” is just a fancy word for a classification system — like the Dewey Decimal System at the library or the way butchers grade meat at the grocery store.)

Dr. Bloom ranked the learner’s ability to do something on six levels, and gave them names — and then provided examples and descriptive words to go along with — like so:

Category |

Example and Key Words |

| Knowledge: Recall data or information. | Examples: Recite a policy. Quote prices from memory to a customer. Knows the safety rules.Key Words: defines, describes, identifies, knows, labels, lists, matches, names, outlines, recalls, recognizes, reproduces, selects, states. |

| Comprehension: Understand the meaning, translation, interpolation, and interpretation of instructions and problems. State a problem in one’s own words. | Examples: Rewrites the principles of test writing. Explain in one’s own words the steps for performing a complex task. Translates an equation into a computer spreadsheet.Key Words: comprehends, converts, defends, distinguishes, estimates, explains, extends, generalizes, gives Examples, infers, interprets, paraphrases, predicts, rewrites, summarizes, translates. |

| Application: Use a concept in a new situation or unprompted use of an abstraction. Applies what was learned in the classroom into novel situations in the work place. | Examples: Use a manual to calculate an employee’s vacation time. Apply laws of statistics to evaluate the reliability of a written test.Key Words: applies, changes, computes, constructs, demonstrates, discovers, manipulates, modifies, operates, predicts, prepares, produces, relates, shows, solves, uses. |

| Analysis: Separates material or concepts into component parts so that its organizational structure may be understood. Distinguishes between facts and inferences. | Examples: Troubleshoot a piece of equipment by using logical deduction. Recognize logical fallacies in reasoning. Gathers information from a department and selects the required tasks for training.Key Words: analyzes, breaks down, compares, contrasts, diagrams, deconstructs, differentiates, discriminates, distinguishes, identifies, illustrates, infers, outlines, relates, selects, separates. |

| Synthesis: Builds a structure or pattern from diverse elements. Put parts together to form a whole, with emphasis on creating a new meaning or structure. | Examples: Write a company operations or process manual. Design a machine to perform a specific task. Integrates training from several sources to solve a problem. Revises and process to improve the outcome.Key Words: categorizes, combines, compiles, composes, creates, devises, designs, explains, generates, modifies, organizes, plans, rearranges, reconstructs, relates, reorganizes, revises, rewrites, summarizes, tells, writes. |

| Evaluation: Make judgments about the value of ideas or materials. | Examples: Select the most effective solution. Hire the most qualified candidate. Explain and justify a new budget.Key Words: appraises, compares, concludes, contrasts, criticizes, critiques, defends, describes, discriminates, evaluates, explains, interprets, justifies, relates, summarizes, supports. |

Source: http://www.skagitwatershed.org/~donclark/hrd/bloom.html

So, any time you want to teach somebody something, you can think about measuring what they can do based on these six levels. They range from very low “knowledge” to very high “evaluation”. To make that a little easier to understand, let’s try a couple of examples.

Suppose your job was to teach people to tie their tennis shoes. Here’s what that might look like in the different levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy:

|

Knowledge: Recall data or information. |

Can identify tennis shoes from loafers. |

|

Comprehension: Understand the meaning, translation, interpolation, and interpretation of instructions and problems. State a problem in one’s own words. |

Can explain why it’s important to tie shoes correctly (“fall down – go boom!”) |

|

Application: Use a concept in a new situation or unprompted use of an abstraction. Applies what was learned in the classroom into novel situations in the work place. |

Can demonstrate how to tie shoes. |

|

Analysis: Separates material or concepts into component parts so that its organizational structure may be understood. Distinguishes between facts and inferences. |

Can compare how to tie tennis shoes and boots with hooks and loops. |

|

Synthesis: Builds a structure or pattern from diverse elements. Put parts together to form a whole, with emphasis on creating a new meaning or structure. |

Can devise how long laces must be by counting number of holes, calf size and knotting/lacing model. |

|

Evaluation: Make judgments about the value of ideas or materials. |

Can compare and contrast use of rawhide laces, nylon laces, catgut and cotton to recommend the best choice for each situation. |

One more example? How about that jet pilot, learning to deal with losing an engine…

|

Knowledge: Recall data or information.

|

Can list the basic steps in engine restart. |

|

Comprehension: Understand the meaning, translation, interpolation, and interpretation of instructions and problems. State a problem in one’s own words.

|

Can give examples of why an engine may have failed, and probable causes. |

|

Application: Use a concept in a new situation or unprompted use of an abstraction. Applies what was learned in the classroom into novel situations in the work place.

|

Can demonstrate the “Hot Engine Restart” procedure in the flight simulator. |

|

Analysis: Separates material or concepts into component parts so that its organizational structure may be understood. Distinguishes between facts and inferences.

|

Can analyze cockpit instrumentation to determine most likely cause of failure and choose best restart mode. |

|

Synthesis: Builds a structure or pattern from diverse elements. Put parts together to form a whole, with emphasis on creating a new meaning or structure.

|

Can combine engine-out experiences to generate emergency plan for unforeseen circumstances. |

|

Evaluation: Make judgments about the value of ideas or materials.

|

Can land plane in the Hudson River and have every single person walk away alive. |

So, this is why it’s sometimes important to think a little bit further than just lecturing to people about what it is that you want them to know. And that means things like getting their little fingers dirty, testing out concepts, discussing and experimenting, role-playing, tearing it apart, putting it back together, breaking it, fixing it, building a completly new model — all the stuff that takes more time and costs more money.

{ 3 comments… read them below or add one }

Thanks for this informative introduction to Bloom’s Taxonomy. I thoroughly enjoyed it. Still, I find the description of the form and function of an academic lecture to be misformed.

The issue with the assessment of lectures here is not whether ‘the lecture’ is an effective learning tool, but rather that the lecture belongs to a specific cultural tradition in which personal responsibility is the inverse of non-scholarly pedagogics.

What I mean by this is that in the context of say primary or secondary education the maxim reigns that “there is no such thing as a bad learner, there are only bad teachers”. In contexts such as these, we consider it the instrcutor’s responsibility to deliver the material in such a way as to cater to the learners’ needs.

The inverse is true in many scholarly applications including e.g. the lecture or German academic literature to name another. In these contexts, the scholar adheres to scholarly constructs of presentation, be it a quotation system like MLA, and it is the recipient’s responsibility to comprehend, analyse and evaluate the material.

Instead, this article maintains that such formats are now antiquated and ineffective. But in saying that, this article misrepesents through ignorance the function of intellectual responsibility.

Ah, the MLA! Haven’t worried about that since the Master’s Degree — talk about cruel and unusual punishment…

I object to your premise that I misrepresent through ignorance — I misrepresent through stupidity, sloth, and a general unwillingness to do any serious research into my topics. But that’s neither here nor there.

Your point is well taken. A “pure” lecture does place the responsibility squarely upon the learner (well, “victim” might be a better word) to somehow sit there and take in the golden words and somehow arrange them in long-term memory in a meaningful way. So when I’m lecturing at Heidelberg I’ll be careful to put the kibosh on any job aids, interaction or any assessment-and-remediation models.

But whilst (heard that one on NPR) I’m working in the world of online communication or classroom training, I’ll probably still try to fill the little skulls full of mush in such a way that at least a bit of my content sticks.

Sullenberger worked for USAir not American Airlines.